|

|

China's LEO Constellation Ambitions

Mar 6th, 2018 by

Jose Del Rosario, NSR

In late-February 2018, the China Aerospace Science and Technology

Corporation (CASC) announced plans

to build a constellation of 300 small satellites in LEO for global

communications and other services. The Hongyan (translated as “wild

goose”) constellation, which is targeted to be operational by 2021, was

originally designed for 60 satellites. The current plan expands to 300

satellites reportedly due in part to a deal with Thailand Kasetsart

University and the China Great Wall Industry Corp, a CASC subsidiary.

What is or Will be Hongyan’s Impact on the Satellite industry?

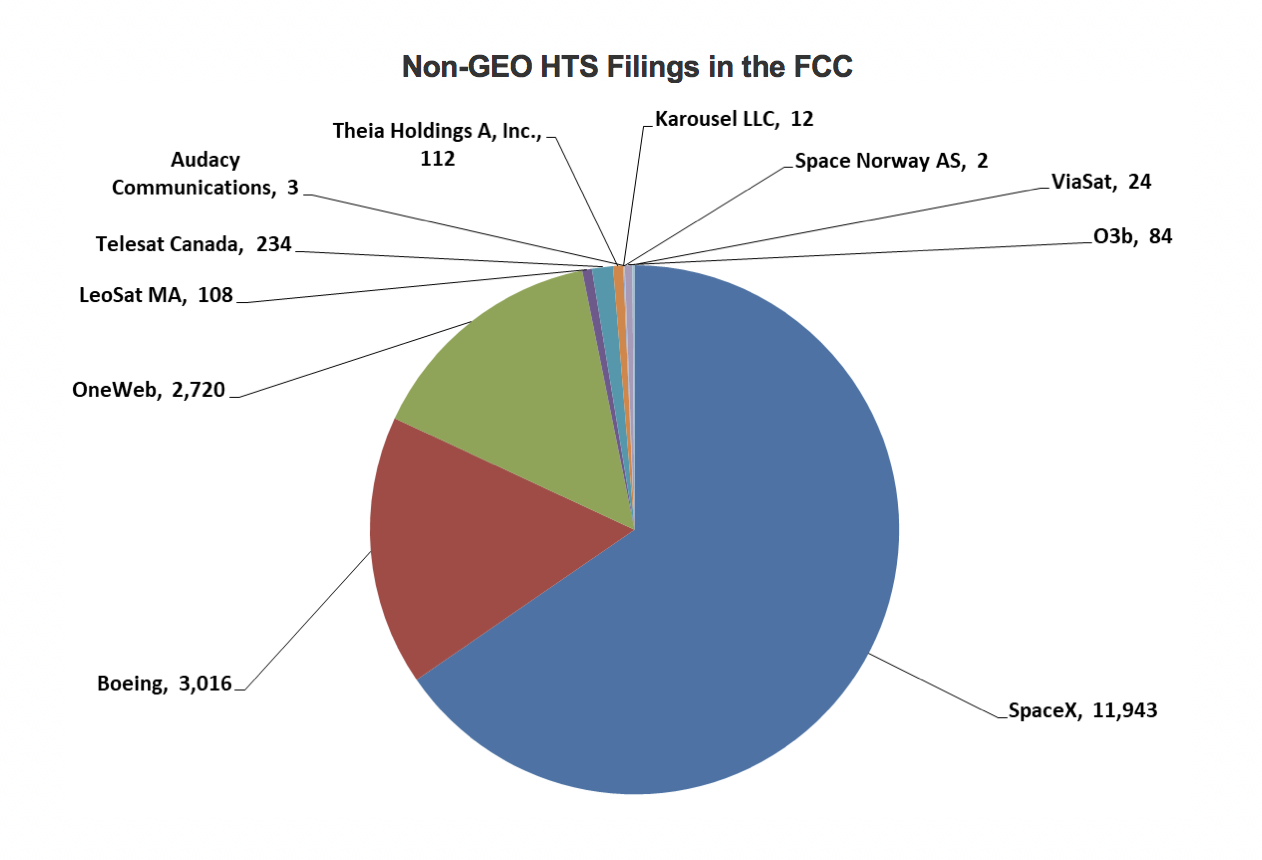

The most visible or at least, the most talked about LEO contenders stem

from the U.S. and Canada, numbering at least 11 with planned satellites

to be deployed at around 18,000. Hongyan’s 300 satellites certainly pale

in comparison to programs that include SpaceX, Boeing and OneWeb that

have filed with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC),

largely targeting broadband access services in efforts to bridge the

Digital Divide.

In terms of market access, the “FCC Players,” as depicted in the graph

above, will likely position the U.S. as an anchor market, and the

Rest-of-the-World could be regarded as secondary targets. Developing

regions are always considered given the need for connectivity; however,

the business case still needs to be closed as market dynamics do not

support a U.S. or Western-style approach. For instance, ARPU levels in

the U.S. cannot be applied to Africa given the macroeconomic conditions

of many countries. Yes, the A and B socio-economic groups can be

targeted and are the low-hanging fruits, but to truly support an ROI

model that reaches the masses, ARPU levels in Africa (and other

low-income populations around the globe) must decline to very low levels

to make the service affordable. And let’s not forget equipment

costs, which are also a prohibitive expense that must be included in the

equation.

In Comes China

The “FCC Players” primary markets will likely not be threatened by

Hongyan as it will likely not gain market access in the U.S. and Canada.

In fact, Hongyan is not looking to provision services or compete in the

U.S. and Canada anyway. Instead, China is looking at Eurasia via the

“One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative as well as African and Latin

American countries as part of its soft power projection and overall

thrust of gaining economic, political and security ties with an ever

expanding number of countries that are willing to be part of its sphere

of influence. So, the question is, can China’s Hongyan

constellation change the market dynamics such that low ARPU can be

achieved as well as equipment costs be made affordable? We don’t

know as China has not released many details of its satellite programs

and its go-to-market strategy. But what we do know is that China has

made deals in Nigeria and Bolivia (and will likely make other deals

outside the OBOR footprint) where financial arrangements have made

procurement, launch and satellite service provisioning possible.

And

here is where the threat lies

for the “FCC Players.”

Hongyan will not apply U.S. or Western-style

market penetration strategies but follow or create a new market dynamic

where pure market forces will not be applied. In a sense, China

will change or un-level the playing field.

These can or will include financing packages that minimize risks to

their “clients” that will favor Hongyan over offerings made by the “FCC

Players” based on traditional or Western-style ROI strategies in Eurasia

and other low income countries across the globe.

Bottom Line

China’s space program and satellite communications

initiatives, including the deployment of Hongyan, are not based on

Western-style market economics. In fact, it can be argued that gaining

positive ROI is not the end goal of China’s space program but primarily

the projection and increase of its power and influence across the globe.

The side effect of this is to potentially

undermine the value proposition of Western players that go by

traditional market rules and strategies,

specifically in the Eurasian, African and Latin American regions as well

as other low-income countries that cannot afford high-speed connections.

Additionally, in NSR’s China Satcom Markets (CSM) report, Chinese

state-owned companies are forecast to manufacture and launch over 800

Gbps of GEO-HTS capacity by 2026, with much of this coming over these

regions.

And as seen from the deal between Thailand Kasetsart University and the

China Great Wall Industry Corp., countries and institutions are willing

to play ball with China to further their goals. In fact, it is highly

likely that another Chinese constellation will enter the market, and/or

Hongyan can be increased further from its current 300 to rival the

largest planned constellations such as SpaceX and Boeing.

The full backing and power of the state in terms of program development,

funding and the sheer persistence in meeting China’s space policy goals

are what companies in the West will contend with in a changing

marketplace.

|

|