Asian Satellite Market Update

May 17th, 2017 by

Blaine Curcio, NSR

This week saw the successful

launch of the fourth Inmarsat Global

Xpress satellite. This launch was noteworthy because the

company, by virtue of successfully launching the first three,

has already achieved global HTS coverage. The coverage of the

fourth—planned to address areas of high demand—has been a

topic of much speculation over the past year or more,

with Inmarsat CEO Rupert Pearce

noting

last week that the satellite could potentially see its mission

changed during its in-orbit life, but that it will initially be

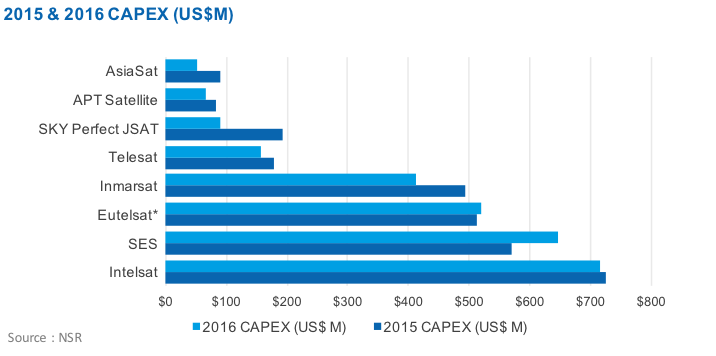

placed over Europe, Middle East, and Africa. As discussed in

NSR’s Satellite Operator Financial Analysis, 7th

Edition, this is the continuation

of a period of elevated CAPEX for Inmarsat, with the company

expected to continue adding capacity in the form of its

Inmarsat-6 duo of satellites. As discussed in the SOFA-7 study,

the company was initially planning to launch the satellite over

APAC, but these plans changed markedly due to a combination of

geopolitics and market conditions that are coming to a head

today. noting

last week that the satellite could potentially see its mission

changed during its in-orbit life, but that it will initially be

placed over Europe, Middle East, and Africa. As discussed in

NSR’s Satellite Operator Financial Analysis, 7th

Edition, this is the continuation

of a period of elevated CAPEX for Inmarsat, with the company

expected to continue adding capacity in the form of its

Inmarsat-6 duo of satellites. As discussed in the SOFA-7 study,

the company was initially planning to launch the satellite over

APAC, but these plans changed markedly due to a combination of

geopolitics and market conditions that are coming to a head

today.

The Belt & Road

This is in fairly sharp contrast to late 2015, at which time

Inmarsat was welcoming Chinese President Xi Jinping to the

company’s offices in London, announcing the establishment of a

framework that could see a deal that was, at the time, rumored

at the time to be for 15-years and hundreds of millions of

dollars for a “New Silk Road” (also known as One Belt, One Road,

or OBOR) mobile communications agreement. Up to this point,

Inmarsat has been kept waiting for a windfall deal as part of

China’s $40 billion “New Silk Road” fund, or the $122 billion

pledged infrastructure investment at the recent Belt and Road

Forum in May 2017.

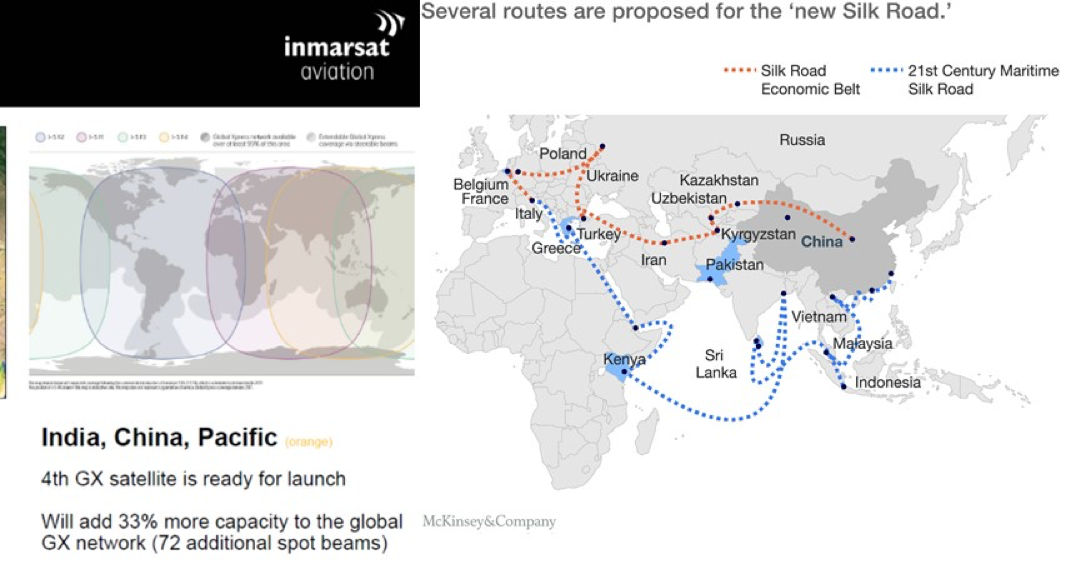

Which brings us back to Inmarsat’s successful launch of

Inmarsat 5F4 this week. It is reasonable for Inmarsat to assume

that mobility demands in greater APAC will grow at a robust

clip. The Belt and Road initiatives involve significant amounts

of trade via land, sea, and (to a much lesser extent), plane.

These are all verticals that Inmarsat with Global Xpress should

be particularly well-suited to address, with some of the

shipping routes at left showing the diversity of coverage

required. The question, therefore, is what has kept Inmarsat

from following through on its initial plan to launch the 4th

Global Xpress satellite over Asia? The company has, as recently

as earlier this year, shown in presentations an APAC-centric

coverage map for the 4th satellite, such as the map

at right, and it is therefore somewhat surprising they would

decide to launch the 4th satellite initially over

EMEA, even if, up to this point, the company is seen as having

done quite well in these markets with GX. In light of recent

industry and macroeconomic events, however, the move makes

somewhat more sense, and may not bode well for Inmarsat.

Inside the Mind of the Politburo

There are two major factors here that ultimately may be

working against Inmarsat, if the medium-term intention is in

fact to move the satellite over APAC and address mobility demand

related to OBOR and/or the region’s IFC markets. These two

factors are 1) China’s push towards handling ever-more-complex

space matters domestically, and 2) China’s push towards

exporting high-tech goods and services in the future. In short,

space is sexy in China today, and the country’s government sees

a strong space program as a combination of supporting

technological leadership in a key industry and slick party

propaganda, with a strong/strengthening space program playing

into the greater narrative of a strong/strengthening China. The

country is therefore pushing towards developing more

space/satellite capabilities domestically, with this including,

but not limited to, the nation’s first HTS launch earlier this

year, the nation’s first sale of an HTS to a foreign customer

(Thaicom) in late 2016, and the nation’s first apparent

“OBOR-related” satellite sale with a potential 2x deal with

Indonesia earlier this month.

Beyond the above-mentioned “firsts”, China has seen several

domestic players make moves to address the mobility markets via

GEO-HTS, with some of the plays looking similar (albeit less

local) than Inmarsat’s. This includes APT Satellite’s

Ku-band GEO-HTS system, which is initially planned to

be one satellite targeting APAC (Apstar-6D, for launch in 2019),

and potentially several more aiming for global coverage. As

discussed in NSR’s SOFA7, APT Satellite is in excellent

financial condition given its low degree of leverage, and thus

would be likely capable of pursuing a program should demand

prove to materialize. Overall, the implication here is that

China is likely to prioritize domestic capacity for its

mobility needs, with this already being the case in

video broadcast, VSAT networking, and any other verticals that

ChinaSat (and to some extent APT Satellite) is able to serve.

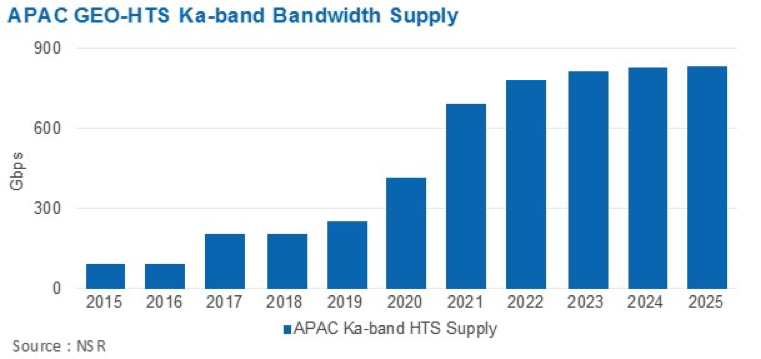

The Impact on Greater APAC Supply

Perhaps more significant, however, is the potential impact on

the overall APAC supply/demand balance. Ultimately, it appears

that satellites for “broadband connectivity” purposes have in

many instances become a politically acceptable way of spending

infrastructure/R&D funds, and China has recognized that there is

a market here, even more so if Chinese Ex/Im-type loans are

oftentimes paying for these satellites, backed by natural

resources or some other tangible good. This could

radically alter the supply picture in Asia-Pacific,

with the recently announced satellites over Indonesia claiming

over 100 Gbps of capacity, according to a presentation at the

recent APSAT conference.

This capacity is oftentimes country-focused, or at most

region-focused, but the impact on supply/demand balances within

these countries or regions can be significant. Conservatively

speaking, total GEO-HTS Ka-band supply over APAC will reach 900

Gbps by the end of the decade, though with much of this being

government-launched satellites, including NBN (160

Gbps). While demand may be robust when considering

government-mandated programs with subsequent government funding,

this funding will also factor in on the supply side, with

countries like Myanmar and Bangladesh being involved in various

stages of satellite programs. Ultimately, operators will

need to find some way of differentiating their capacity

in a market that is becoming increasingly crowded, with some of

the entrants not playing purely for profit.

Bottom Line

The launch of the 4th Inmarsat Global Xpress

satellite occurred at a very busy time for the satellite

industry in Asia Pacific. Late 2016/2017 has already seen the

order of JSAT-18/Kacific, the purchase by Thaicom of an HTS on

behalf of a client, the firm purchases for national

satellites/private-public-partnership schemes for Indonesia, and

the first HTS launch for China (with another planned next week,

with 70 Gbps of capacity). In addition to this, we saw just last

week the involvement of Sky Perfect JSAT in LeoSat’s

constellation plans with an investment of $100M. What is more,

SoftBank of Japan is undoubtedly the industry’s biggest investor

as of late, with a $1B+ investment into OneWeb, and a potential

$1.7 billion on the table as a proposed investment into

Intelsat.

Inmarsat’s 4th GX satellite is likely to remain

over EMEA until the company obtains some bulk lease within

APAC/China, along the lines of the rumored government contract

linked above. Given the increasing tendency for China to launch

higher throughput capacity—and to finance other countries in

APAC to do the same—it may be more difficult than

originally assumed to find a lease that would justify

such a move. In an industry known to be fairly stable, the

satellite telecommunications industry in Asia is more volatile

than ever today.

|

|