New Metrics for New HTS Models

Jan 13th, 2016

by Lluc Palerm-Serra, NSR

The key metric for satellite operators

has traditionally been fill rates. Fill rates are an accurate

measure of success for widebeam FSS satellites in which video is the

major application as video is constantly beamed and hence fill rates

equate to utilization. An added benefit is that contracts are

long term leading to relatively stable transponder prices.

However, HTS systems focus on serving data traffic, and broadband

demand is concentrated in peak hours, making fill rates a poor

metric for capacity utilization. Furthermore, the large amount of

new capacity being launched creates pricing instabilities. All in

all, fill rates are a poor predictor of success for an HTS system.

If fill rates are no longer applicable, then the question is:

how do satellite operators measure

the success of an HTS system?

One could say that 2016 will be the

year in which HTS goes mainstream. Intelsat will launch EpicNG, and

all big 4 will have HTS capacity (each with completely different

approaches), Inmarsat started the year launching commercial services

on its GX constellation, and regional players are accepting this new

technology either with entire HTS satellites or hybrid payloads.

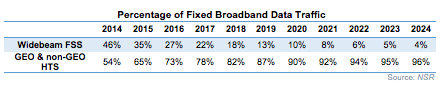

Most of the data traffic boom forecasted for the coming years will

be captured by HTS systems. According to NSR’s VSAT and

Broadband Satellite Markets, 14th Edition Report, in

2014 HTS systems already accounted for 54% of data traffic for fixed

broadband services, but this contribution will grow to reach an

astonishing 96% in 2024 illustrating why

an HTS play is essential for satellite

operators to stay relevant in data verticals.

HTS needs to be part of the

strategy for any satellite operator targeting data applications.

But these investments should not be guided by legacy performance

indicators like fill rates. Focusing too much on maximizing fill

rates would lead to wrong strategic directions (for example) by

exclusively targeting low-value high-volume applications like

consumer broadband causing congested beams at peak hours with poor

quality of service while missing the high-value opportunities in

verticals like mobility or wireless backhaul.

It is time for a new set of metrics

adapted to the new business models growing around HTS ecosystems

that puts satellite operators on the right track for growth and

profitability.

KPIs for Capacity Utilization

Data applications present great

variance between peak and valley capacity consumption.

This makes fill rates difficult to define and of low relevance for

measuring capacity utilization. Similar to congestion in

transportation during rush hour, when demand outweighs capacity,

consumer broadband demand becomes concentrated during evening hours.

This was a common issue for several operators in 2015. For instance,

Eutelsat’s KA-SAT reached saturation at peak hours in its most

popular beams but continued to add enterprise customers and academic

institutions. Similarly, ViaSat also suffered from beam congestion

but continued to attract more air mobility services.

Luckily, different verticals have different usage patterns. To

add even a further layer of complexity,

geographical distribution of users

must also be considered with different beams presenting wide

differences in the number of subs or with mobility customers

following changing routes like the reversing westbound and eastbound

flows in the North Atlantic Air Corridor.

To maintain service quality and accommodate room for growth,

satellite operators need to plan capacity to meet peak rates, rather

than average rates. However, this presents some key challenges. As

outlined in NSR’s VSAT and Broadband Satellite Markets, 14th

Edition Report, close to 90% of the data traffic for satellite

broadband markets will be originated by consumer broadband. Because

of the dominance of one vertical over others, the gap between peak

and average traffic is growing. Additionally, consumer broadband

consumption composition is also changing, accelerating the

consumption of video further increasing this peak-to-average ratio.

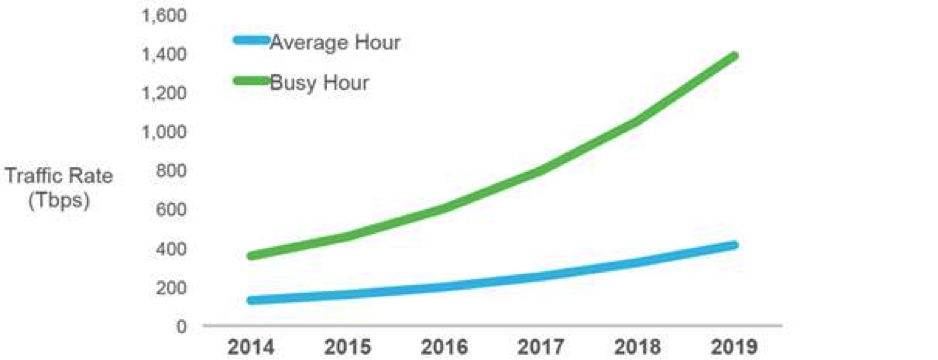

To put this in context, global IP busy-hour traffic will grow at a

CAGR of 31% compared with 26% for average traffic, according to

Cisco’s Visual Networking Index 2015.

Source: Cisco Visual Networking Index

Satellite operators need to create new measures for operational

efficiencies. An operator

that is able to combine different applications to reach a balanced

“peak usage” vs. “average usage” would mean that it is best using

the capacities of its system.

However, it also must be noted that “peak usage” must maintain some

margin over “peak capacity” to ensure service quality and room for

growth. With satellite operators’ increased visibility over client’s

usage patterns through Managed Services, attracting a balanced

customer base should become an objective for these new systems.

Given the growing peak-to-average ratio in capacity consumption, one

can understand the high

interest of satellite operators in flexible satellites

than can shape the beams to follow the capacity demand usage

patterns.

From Measuring Volume to

Revenue Generation

Every data vertical has very different

pricing and revenue generation dynamics. It would be difficult to

have an accurate picture of performance by only looking at

operational efficiencies when comparing verticals with such

different revenue trends as consumer broadband (high-volume,

low-margin) with backhaul, trunking or mobility (low-volume,

high-margin). Measuring

only volume (fill rates) can’t predict if an HTS system would be

profitable.

In order to capture this variance in

the capacity to monetize the Mb depending on the vertical, it is

necessary to visualize the

“Average Revenue per Used Mb”.

This figure would show the capacity of a satellite operator to

attract high valuable customers.

What’s the Role of Technology,

Capacity Supply & the Changing Cost Equation?

There are HTS systems specifically

built for some verticals like EchoStar 17 for consumer broadband or

Inmarsat’s GX for mobility. The design criteria for these systems

are very different, from purely maximizing throughput to maximizing

coverage area. Accordingly, it is necessary to have a wider

perspective when comparing HTS systems and not only look at revenue

generation but also compare the systems’ costs. Comparing “Average

Revenue per Used Mb” with

“Average Cost per Supplied

Mb” would give a vision of

the Return on Investment the system can achieve.

Satellite operators have recently put a lot of emphasis in

reducing the CAPEX/MHz ratio of their new satellites. Electric

propulsion, payload scalability or launch costs have been some of

the fronts used to cut costs.

Last but not least, the shift from a B2B to a B2C industry

occurring with the rise of consumer broadband comes with new cost

structures, especially the high operating costs of customer

acquisition and service of a B2C business compared with old

CAPEX-intense B2B cost structures.

Bottom Line

The wide variance in usage patterns of

HTS systems together with the pressure on pricing makes fill rates a

meaningless measure of success for HTS architectures. Measuring

volume alone is no longer relevant if it’s not accompanied with a

measure of how effective

the utilization of the assets is and what net margin this volume can

produce.

HTS is opening new markets for satellite operators, and the

industry needs to completely re-think the business models to serve

these green fields. This includes how to measure success.

There is currently no single

metric or a combination of metrics that best measure HTS success.

However, this will surely be a topic that will be vetted by the

industry in the coming months, both for internal performance checks

as well as for external financial benchmarks in formulating

investment decisions.