The New Drone Diplomacy

Jan 29th, 2015 by

Prateep Basu, NSR

U.S. President Barack Obama’s recent visit

to India amidst much fanfare was more than symbolic of

the regional geopolitics and his ‘Asia Pivot’ policy.

Lurking somewhere behind the bonhomie between the two

Heads of State was the fate of defense deals, including

highly sought after Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS).

India, like other Asian powers Japan and

South Korea, has been pushing for a deal for 8 MQ-4C

Global Hawks for safeguarding its maritime sovereignty.

Unlike India, long term U.S. partners Japan and South

Korea have already received clearance for procuring the

Northrop Grumman-made UAS, which boast superior

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR)

capabilities.

Rewind to last decade, and the word

‘drone’ would have struck fear and spite among many due

to its extensive use in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

Their utility in protecting troops from dangers in war

zones, and providing ISR data have proven to be

unparalleled. But today, drones are increasingly finding

new applications such as disaster management,

humanitarian peacekeeping, and homeland security to name

a few; however, it is Defense & Intelligence (D&I) that

continues to be the major interest of States. This has

made calls louder for relaxing the outdated Missile

Technology Control Regime (MTCR), under which the trade

of these UAS falls.

The U.S. sale of High Altitude Long

Endurance (HALE) and Medium Altitude Low Endurance

(MALE) UAS such as the Global Hawk and the Reaper means

geopolitics and foreign policy will continue to

play a major role in the proliferation of UAS.

Under pressure from aerospace and defense firms, the

U.S. Government is using its diplomatic relations to

exempt friendly states from the draconian MTCR,

as Israel and China race ahead in the global trade of

UAS in this multi-billion dollar industry. And this

raises the question – are we seeing a new kind

of bilateral relationship between East and West where

drones are diplomatic tools?

The Key Words

UAS are distinguished according to their

payload capability, range and endurance. UAS have proven

their utility in both war zones, as well as for

commercial applications like monitoring of oil & gas

pipelines and assisting in wildlife conservation.

Despite a fairytale story of the rapid

evolution of UAS in the last decade and half, their

usage has been limited by two roadblocks –

availability of satellite bandwidth and airspace

regulations. With greater payload

sophistication, UAS have become more and more bandwidth

hungry devices, which has prohibited the use of a full

fleet. For example, each Global Hawk can easily

consume 50+ Mbps of bandwidth, which amounts to over

40MHz of traditional FSS capacity. To add to the

picture, most HALE and MALE UAS are designed to operate

in Ku-band, and this trend is expected to continue given

the latency in changes made to UAS designs. Airspace

regulations have been less of a concern for the main

market, which is D&I.

And We Are Talking about Them

Because…

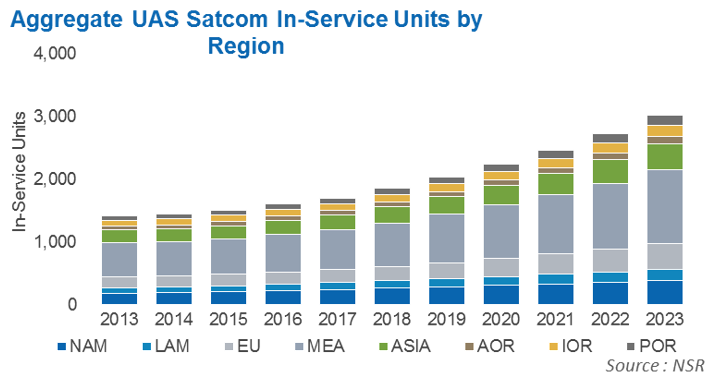

In its recent report titled

Unmanned Aircraft Systems via Satellite,

NSR predicts the number of these larger, high

performance UAS will more than double during the

period 2013-2023, as countries stack up their

defense arsenal, but this will have to be complemented

by capacity planning over regions of growth.

Due to ongoing conflicts in the region,

the Middle-East and Africa will continue to be where

most UAS are deployed, but Asia and Europe are expected

to have considerable growth in this sector mainly due to

territorial disputes, and anti-terrorism activities.

The Bottom Line

Diplomacy using drones may be a new U.S.

tool, but shortage of capacity to support UAS operations

is not. The recent drone acquisition plans of countries

in Asia and the Middle-East provide an opportunity on

which commercial satellite operators can capitalize, and

add a bonus to President Obama’s new drone diplomacy

efforts. Availability of bandwidth and

throughput will however continue to remain the keywords

for these efforts to succeed.