What Happens When HTS

Beams Fill Too Fast…or Too

Slow?

Oct 20th, 2014 by

Prashant Butani, NSR

They may seem like

a new trend, but High Throughput

Satellites (HTS) first launched

in August 2005 with iPSTAR,

nearly a decade ago. Since then

there has been a learning curve

that HTS has been through, and

to some extent is still on.

Applications, architectures,

business models, orbits and

coverage areas have all been

tweaked and tested.

All this while, being the newbie

has given some leeway to HTS in

terms of fill rates. Some beams

have maxed out at launch while

others have struggled to find

customers. What impact does this

have when operators plan

replacements or even entire

fleets of HTS? What do they tell

investors for whom HTS is the

new “must have”? Is bigger

always better? Is global the new

local?

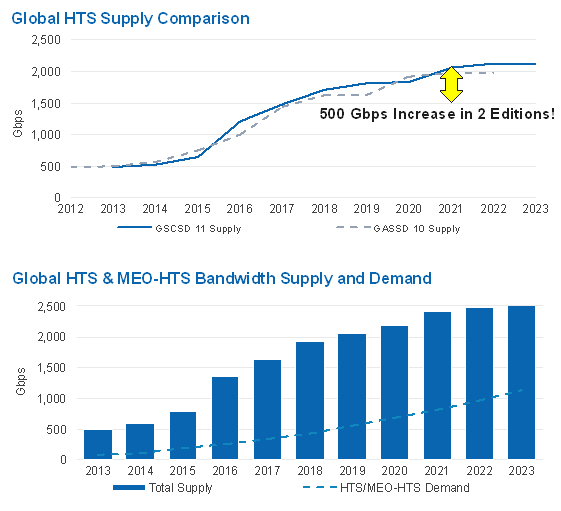

NSR’s

Global

Satellite Capacity Supply &

Demand, 11th Edition

report has forecast HTS supply

and demand for over 6 years now.

The graph below shows how our

forecasts have been revised

upward of 500 Gbps in just two

years. Also shown below is NSR’s

forecast of fill rates across

HTS globally, a figure that

never

crosses the 50% mark

in the next decade.

Does this mean that beams aren’t

filling up quickly enough?

The

answer depends on which beam one

is talking about. Every

satellite operator launching HTS

has learned, what is now, a

seemingly obvious lesson.

Some

beams fill up faster than others

while some lag behind.

Be it closed systems (ViaSat,

Jupiter) or open ones (Avanti,

Yahsat), there will always be

beams that are oversubscribed

while others have limited

demand. For Government projects

like NBN, this has resulted in

projections for system cost

being revised

multiple times. These systems

aim to provide “broadband access

to all”, which means different

things in different beams. For

private players like Thaicom,

this means

going

after seemingly unconventional

applications

–

e.g. DTH in small countries

under a single beam. Business

models have had to change from

closed to open in order to fill

up beams. Governments have had

to delay projects, or supplement

them with military payloads.

Success has come to rest upon

two factors:

-

How many beams can you fill

up

without causing degradation

of service? AND

- How can you

limit under-utilized beams?

(i.e. not just burn up fuel)

What does this mean for future

missions?

NSR

believes that HTS systems will

go two ways depending on the

approach (and investment

profile) of the operator. Some

large operators, like Intelsat

and Inmarsat have

gone

global.

Cover all land masses and oceans

giving them enough leverage

between regions to fill up beams

with country-specific demand.

Overlay these with “regional”

beams allowing for traditional

FSS-type sales that

de-risk the HTS mission.

This is capital intensive, but

the upside is the ability to

offer their largest customers

the advantages of a single HTS

system, no matter where they

choose to operate.

Other large

operators (SES and Eutelsat)

have chosen

more

tailored HTS payloads,

usually with an anchor tenant

consuming the vast majority of

the spot beam capacity even

before launch. This is a

lower risk approach but one that

changes the sales strategy to

targeting specific applications

and customers within a region or

country rather than truly global

users. Smaller operators like

Avanti, Yahsat and Thaicom have

gravitated towards the latter

model –

small, focused payloads with

emphasis on pre-sold capacity

ensuring most beams remain

filled from day one.

NSR believes that

the latter (more focused) model

will remain popular, increasing

competition in the near term.

This does not take away from

global systems like EpicNG and

Global Express, and both have

healthy backlogs already.

However, these will tend to rely

upon moving existing customers

to HTS capacity rather than

aggressively competing with an

“ever falling” cost per bit. The

bulk of the launches therefore,

will be regional HTS payloads

over growing economies with

latent demand for broadband.

Bottom Line

HTS

systems will continue to find

their ground in a market that

has so far been dominated by

widebeam FSS. They’ve found a

bandwidth hog in broadband but

have been challenged by beams

filling up too fast and too

slow. When terrestrial

technologies experienced a

similar surge in demand they

simply

built

as much capacity as possible

either laying fiber or

installing towers. Satellites do

not have this advantage of

waiting for demand to build up

in a sub-region before investing

in a tower or PoP. Neither can

they upgrade hot spots on the

fly. However, future missions

will definitely adopt a

focused and targeted approach

to putting up HTS beams – a

coming of age of sorts.